What constitutes the nation-state? Conventional answers to this question propose that the nation-state involves two key elements: first, the cultural and imaginative construction of the nation as a community and, second, the state apparatus that governs the territory within which this national community resides. When the nation is predominantly imagined as a homogeneous ethnic community, the state operates to reinforce this homogeneity within the bounds of its sovereignty. However the nation can also be imagined as something more ethnically inclusive. Here citizenship might be premised upon residence rather than ethnic heritage. The history of the nation-state is defined by specific versions of both the ethnic and the inclusive state. How might we consider Palestine in relation to these observations?

Palestine can be understood as a nation in the sense that it is imagined to exist by millions of Palestinians living in what was Mandate Palestine and in the Palestinian diaspora. Palestine is imagined as a connection between a people and a place that has not yet been realised in the form of a state that controls a contiguous sovereign territory. What is currently called Palestine is a not a state because those places within former Mandate Palestine where Palestinians live, or where the Palestinian Authority has administrative control are effectively under Israeli rule. The Oslo process of the 1990s created some of the institutions constitutive of the state and involved the deployment of official symbols of nation-statehood. Yet so much of the state-apparatus remains absent. There is no Palestinian currency, or Palestinian passport. Moreover Palestine is not diplomatically recognised. In official terms it has no international existence. The Israeli occupation denies Palestinian statehood, maintaining a gap between the imagined nation and the state that is aspired to.

Khaled Jarrar’s project Live and Work in Palestine involves a symbolic gesture that aspires to bridge this gap between imagined nation and actualised state. The artist takes on the role of the representative of the sovereign who grants permission to foreigners to reside and work within Palestine. To do this Jarrar has created an official looking stamp that bears the slogan ‘State of Palestine’, which he uses to stamp the passports of non-Palestinian visitors to Ramallah where he lives and works. Thus Jarrar pretends to be the one who controls the border that demarcates the inside and outside of a sovereign territory. The actual border where passports are stamped with the mark of the sovereign is in reality completely controlled by Israel, yet by stamping passports Jarrar contests this border regime.

At a fundamental level, Jarrar also contests what Baruch Kimmerling has called ‘the politicide’ (Baruch Kimmerling, Politicide: Ariel Sharon’s War Against the Palestinians, New York and London: Verso, 2003) of the Palestinians through which the Israeli state has worked to destroy the Palestinian capacity to organise themselves in political terms. Since the early 1990s this politicide has involved the radical fragmentation of Palestinian space within the West Bank, establishing a spatial reality that militates against the establishment of a Palestinian border. As Ronen Shamir observes, ‘the governmental logic of the occupation is an “antiborder” logic.’ (Ronen Shamir, ‘Occupation as Disorientation: The Impossibility of Borders’, in Adi Ophir, Michal Givoni, and Sari Hanafi, eds., The Power of Inclusive Exclusion: Anatomy of Israeli Rule in the Palestinian Occupied Territories, New York: Zone Books, 2009)

Thus the Israeli state has created a paradoxical situation through which a tightly controlled border regime – the most important locations of which are at Ben Gurion Airport and the Allenby Bridge Crossing – encloses an anti-border condition that is synonymous with the denial of the state of Palestine. As another Palestinian artist, Khaled Hourani has stated: ‘I exist in a place that is not a state … full of checkpoints, border crossings and barricades. When there is no state, there are no borders.’ (Khaled Hourani, statement for the ‘Liminal Spaces’ project)

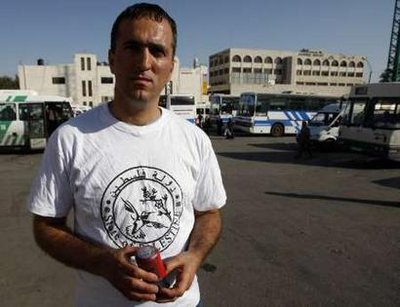

By waiting for foreign visitors at Ramallah central bus station and requesting if he can stamp their passports, Jarrar enacts the setting up of an alternative border, asserting his agency as a creative and political subject, and attesting to the fact that the long-standing Israeli attempt to suppress Palestinian political nationalism is an incomplete and in fact failed venture. If Jarrar’s project effectively highlights the lack of Palestinian sovereignty, it also asserts the ever-present potential of this sovereignty in the future. The legend ‘State of Palestine’ exists in the passports stamped by Jarrar as a phantasmic premonition of what might be.

Yet Live and Work in Palestine does not simply entail the act of stamping passports in Ramallah and the stamped passports themselves. It also involves the moments where these passports are used to cross the Israeli controlled border. Jarrar’s project parodies the Israeli border regime when he stamps passports in Ramallah and also brings this parody into an unpredictable encounter with the official Israeli border at Ben Gurion Airport when these passports are scrutinised by the ‘petty sovereigns’ (Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso, 2006, pp. 56-60) of the Israeli state. Given the nature of security procedures at the latter location, travellers carrying the unofficial stamp of the phantom Palestinian state in their passports are understandably anxious about how the representatives of the Israeli border regime will react. What will the Israeli security operatives do? Will they ignore the stamp, or will they take it as a sign that checks and questions must be intensified? As part of his project, Jarrar has not only been photographing people with their freshly stamped passports, but also collecting reports of their experiences at the Israeli controlled border through the project’s Facebook page.

Jarrar also plans to extend his project through the nomination of international ‘ambassadors’ for his phantom state, who will be sent a stamp and instructed to stamp passports in their own countries. Through this spatial extension of the project the effects of the project will also be expanded. More people might hear about it, there might be more news stories about it that there have already been, so that the project becomes a spatially dispersed set of actions and effects involving people stamping passports, stamped passports, instances where these passports are scrutinised by border officials, and instances where the project becomes a story to be told. This story is both about what Jarrar has been doing and the lack of a Palestinian state that his project highlights.

The nomination of people as ambassadors for the project also suggests that the phantom Palestinian border can be set up anywhere. This emphasises that a real Palestinian border exists nowhere. Passports can be stamped with the legend ‘State of Palestine’ everywhere, because the state of Palestine currently exists nowhere. In her discussion of the Israeli checkpoint system, Ariella Azoulay has suggested that to suppress the possibility of a proper Palestinian border the occupation regime has created multiple points of division that often have the appearance of a border. Thus she observes that ‘the border passes wherever a Palestinian body stands.’ Continuing: ‘Every time a Palestinian seeks to travel, Israel takes advantage of the opportunity to reassert its sovereignty. There where he would like to live his life, an ad hoc border-marker is posited – not a borderline but a border-point, a “spot”.’ (Ariella Azoulay, ‘Determined at Will’, in Sharif Waked, Chic Point: Fashion for the Israeli Checkpoints, Tel Aviv: Andulas Publishing, 2007, p. 151) Jarrar’s project mimics and at the same time inverts this system of ‘border-points’, by setting up border-points of his own that enable the assertion of a phantom Palestinian sovereignty. Wherever he, or his ambassadors decide to stamp passports is where the border is. If the checkpoint is the oppressive manifestation of Israeli sovereignty over Palestinians and Palestinian land that also asserts the antiborder condition that is the occupation, then Jarrar’s project contests this sovereignty and its denial of a proper border. Both the checkpoint system and Jarrar’s project attest to the lack of a Palestinian border. Yet unlike the former, the latter is not aimed at maintaining this situation, rather it is concerned with highlighting the lack of a Palestinian border and simultaneously providing a symbolic the solution to this situation.

Jarrar’s project is politically serious. It is aimed at having an impact upon the political situation that holds the possibility of a state of Palestine in abeyance. Yet the project is also conceived as art. It is this status as art that might provide an alibi to the traveller with a ‘State of Palestine’ stamp in their passport when they pass through the Israeli controlled border. The response that the stamp is art could potentially be disarming. Under such conditions the category of art would provide a space of relative protection within which things can be done that might not be possible elsewhere. Here the apparent inconsequentiality of art in political terms means that it has the potential to be of political consequence. The artistic project that parodies the operations of the sovereign state and highlights the absence of Palestinian sovereignty can constitute an alternative space for the assertion of Palestinian rights. Through this the artist can become a new kind of political agent.

Having made these observations, it should be stressed that the Live and Work in Palestine project is not politically prescriptive. The project is about raising questions rather than providing answers. The legend ‘State of Palestine’ does not tell one when, or how this state will come into being, or what kind of state it will be. Will the state of Palestine come into being through a two state settlement between Israel and the Palestinian Authority, or will the Palestine of the future involve some sort of one-state or binational entity? Who will this Palestine be for? Will it just be for the Palestinians, thus constituting a new version of the ethnically exclusive nation-state, or will it be an inclusive state based on residency? A statement made be Jarrar on the project Facebook page suggests that his ideal is some version of the latter kind of nation-state. Thus he writes: ‘I need one state for all so its Palestine for all.’ Who will this ‘all’ be? Palestinians, Jews, others? Whatever the answers to these questions might be, Jarrar’s project attests to the reality that the ongoing Israeli occupation is not only unjust, but also untenable. For a just solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to be achieved, Palestine must become a political reality. For those people guided by any sense of political justice, this is beyond question.

very very interesting artistic and political work! I also read in DOX magazine (summer 2012 n°94) about the documentary Khaled Jarrar is finishing, we hope to watch it soon!

cath.hess from geneva films festival PALESTINE: FILMER C’EST EXISTER

By: catherine hess on October 24, 2012

at 12:00 pm

Thanks for the comment and for the link to DOX magazine. Khaled has shown me some sections of the documentary film and I look forward to seeing it in full.

Simon

By: simonsteachingblog on October 25, 2012

at 1:30 pm

Reblogged this on occursus.

By: PlastiCités on September 10, 2013

at 9:30 pm