In 2006 Mohammed Khatib, a leading member of the Bil’in Popular Committee,

wrote on the Bil’in village website:

‘We refuse to be strangled by the wall in silence. In a famous Palestinian short story by Ghassan Kanafani, “Men in the Sun,” Palestinian workers suffocate inside a tanker truck. Upon discovering them, the driver screams, ‘Why didn’t you bang on the side of the tank?” In Bilin, we are banging, we are screaming … Please stand with us.’ (quoted in Tanya Reinhart, The Road Map to Nowhere: Israel/Palestine Since 2003, Verso, 2006)

This use of Kanafani’s story as a metaphor for the situation of Palestinian villages like Bil’in that have been severely affected by the construction of the West Bank barrier reminds us of just how potentially isolated and silenced Palestinian communities in the occupied territories can be. It also reminds us that many of these communities, with Bil’in being exemplary amongst them in recent years, have resisted this isolation and silence over their plight.

An important function of the Israeli regime of control in the West Bank is to suppress both the Palestinian national movement and forms of popular politics that depend on people making links over distances and acting collectively. The system of closures, curfews, and checkpoints combined with the cantonisation of the West Bank through the construction of barriers, bypass roads, and the settlements themselves are not only about establishing a grid of Israeli military and civilian domination over the territory, but also about dividing Palestinians from each other and from their potential allies, degrading not only their everyday lives, but also their ability to have a political life. As such, this system is fundamentally part of what Baruch Kimmerling has termed the ‘politicide’ of the Palestinians (Baruch Kimmerling, Politicide: Ariel Sharon’s War Against the Palestinians, Verso, 2003). This situation means that for communities like Bil’in, politics has to a large degree become a matter of developing tactics for overcoming this regime of control and division, finding ways to work with Palestinians from elsewhere in the West Bank and with Israeli activists as well as to make their situation visible in an international context. Communication using different kinds of media has become a key element of their political struggle. The internet has of course been very significant here, but the people of Bil’in have also staked much upon successfully gaining the attention of the conventional news media.

A recent article by Henry Jenkins in Le Monde Diplomatique (7 September 2010) emphasises that the key thing that people in Bil’in have done to attract this media attention is stage what Sean Scalmer has called ‘dissent events’ (Sean Scalmer, Dissent Events: Protest, the Media and the Political Gimmick in Australia. UNSW Press, 2002) in which costumes, sculptural props, and theatrical performances were used to enliven demonstrations and amplify their political message. Jenkins focuses on one demonstration in particular that occurred in February this year when activists dressed up as blue Na’vi characters from the film Avatar as a means of both tapping into the currency of the film and appropriating its narrative involving human military power pitted against indigenous life forms on an alien planet who are defending their land.

Jenkins in fact uses this instance of activists appropriating motifs from popular culture to coin the title for the new category of dissent he calls ‘Avatar activism’.

For Jenkins, this kind of protest tactic involves both a gain and a loss. Gained are affective images taken from the field of popular culture and re-used in a political context that he suggests enable the emotional sustenance of dissent. Lost in the reuse of simplistic imagery, often disseminated through new and old media without adequate contextualisation, is a sense of the complexity of the political situations involved. But as Jenkins adds, such simplistic imagery may well ‘direct attention to other resources.’ Thus viewers of a video of the Bil’in demonstration on YouTube, or photographs of the same demonstration on Flickr might turn to text-based forms of communication as a means of informing themselves about why these images were produced. Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites have suggested that the Abu Ghraib photographs disseminated internationally in 2004 encouraged people to read documents that were already in the public realm, but which had not gained as much attention as they should. Thus they state: ‘Strong images can activate strong reading.’ (Robert Harimen and John Louis Lucaites, No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy, Chicago, 2007) The organisers of the Avatar demonstration in Bil’in aimed to produce strong images that would have an impact upon those who saw them and would attract the attention of a much wider audience. The video of this demonstration posted on YouTube by Bil’in based video maker Haitam Al Katib has received 245,440 views, at the time of writing, as opposed to the video of Naomi Klein’s visit to Bil’in in August 2009 which has received 9,498 views. Taking the motif of blue aliens from a science fiction film and relocating it within the political reality of the West Bank could not be anything but a strong image, generating an uncanny effect and one hopes encouraging reflection and ‘strong reading’ that might help explain what was being seen. But the potential effects of strong images are not restricted to media audiences. The strength of these images can also shape how these audiences encounter them in the media. Thus Kevin Michael DeLuca and Jennifer Peeples have argued that the strong images created by acts of symbolic violence performed by anarchists during the protests against the World Trade Organisation conference in Seattle in 1999 focussed the media spotlight on the concerns of the demonstrators, allowing their ideas to be aired and given a greater degree of serious attention (Kevin Michael DeLuca and Jennifer Peeples, ‘From Public Sphere to Public Screen: Democracy, Activism, and the “Violence” of Seattle’, Critical Studies in Media Communication, Volume 19, Number 2, June 2002). With these considerations in mind, it can be suggested that whatever loss of conceptual understanding occurs through the immediate impact of the images of ‘Avatar activism’ can be made up for in how these images relate to the written word.

Considering Jenkin’s fleeting discussion of Bil’in it should be added that the Avatar demonstration was just one instance in which demonstrators in the village appropriated motifs from other contexts, most of which were not related to popular culture. More usual has been imagery related to the broad historical frame of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and current events related to the occupation. Thus the Bil’in Popular Committee have set up demonstrations themed to reference, for example, the iconography of the Holocaust and the storming of the Free Gaza flotilla.

This affirms that the image repertoire of the Bil’in demonstrators is much broader and more historically and politically aware than the appropriation of imagery from a Hollywood blockbuster might suggest. The key point here is that the people of Bil’in have repeatedly appropriated imagery for their demonstrations that is in some way relevant to their cause and that enables them to not only keep going, but also to break out of their isolation. To do this they have had to constantly innovate themes for their demonstrations and develop new props that can become the focal point for demonstrators and the media alike. What this suggests is that although the imagery used in the demonstrations is often simple and involves the reinforcement of crude binaries between oppression and freedom defined in terms of a contrast between the Israeli state and the Palestinian struggle, this mobilisation of simple imagery is the result of a sophisticated understanding of what resources politically weak agents can mobilise in a long term struggle against the power of a sovereign state. The people of Bil’in have committed themselves to non-violence and consequently have had to turn to other media oriented means of resistance to the classic ‘weapons of the weak’ utilised in the armed struggles of guerrilla and national liberation movements.

I have heard some people describe the demonstrations in Bil’in negatively as ‘theatre’ and a ‘media-circus’. Such descriptions identify the key characteristics of the demonstrations but they fail to understand the significance of media attention for certain kinds of contemporary activism. It no longer seems appropriate to judge political movements on the basis of some notion of political authenticity defined in opposition to the big media and some notion of the spectacle as a negative and alienated product of domination. As Simon Cottle has argued, it is a particular form of spectacle that enables certain kinds of political project to occur (Simon Cottle, Mediatized Conflict, Open University, 2006). This does not mean that politics does not exist outside of the media, but rather that in highly mediatised societies the media take on an important function within political projects whether they are hegemonic, or counter-hegemonic. Nor does it necessarily mean, as Cottle argues, that ‘the co-present public at demonstrations no longer count the most’ as opposed to the ‘mass audience watching and reading public the media coverage at home’ (Simon Cottle, ‘Reporting demonstrations: the changing media politics of dissent’, Media, Culture & Society, volume 30, number 6, 2008). In Bil’in the activism on the ground works in conjunction with, but at the same time differently from the effects of its mediation upon a wider audience. The activism engaged in by the villagers and their allies is the core of the struggle, but this struggle is elaborated through the media, an elaboration that in turn feeds back into the activities organised around the local geography of Bil’in. In particular, media attention keeps the struggle visible, raising awareness about the building of the barrier on village land and providing a modicum of protection against the violence of the state. Under this precarious umbrella of this protection in addition to the minimal shield provided by the presence of Israeli and international activists at particular times, the people of Bil’in have not only been demonstrating for five years, but also filed petitions in the Israeli High Court of Justice, and organised an annual conference on non-violent popular resistance that has involved international and Israeli speakers and delegates. Here the geographically limited core and the mass mediated periphery of the struggle maintain and enable each other. Political realities on the ground and practices of media image production are entwined.

The dissent events organised by the Bil’in Popular Committee often involve an element of playfulness with the intention of courting the media and creating circumstances in which eye-catching imagery can be generated, but this playful image production is always serious in its intentions and itself often involves a dramatisation of the seriousness of the situation by involving the Israeli military in the dramaturgical action. Thus in a recent demonstration blindfolded and cuffed Palestinian, Israeli and international activists positioned themselves in front of the soldiers sent to stop them from reaching the barrier with reference to the revelation in the media that week that a female Israeli soldier had posted pictures of herself posing in front of blindfolded and cuffed Palestinians on her Facebook wall. In front of the assembled media the demonstrators played at being detainees while the soldiers inadvertently became their captors.

Yet this dramatisation of a standard scenario of the occupation soon became reality as the soldiers reacted violently to stone throwing, breaking up the demonstration and arresting one of the blind-folded and handcuffed activists. Thus role-play dramatising the power relations and violence of the occupation was followed and in fact dramatically completed by the actualisation of that power and violence through the actions of the soldiers. Yet one might argue that dissent events of this kind are only completed through being imaged in the media.

Writing about his experiences amongst Palestinian refugees and fighters in Jordan in the early 1970s, Jean Genet emphasised how the Fedayeen were turned into ‘stars’ by the media and how at the same time they were very much aware of their roles within the realm of media images. One Palestinian fighter states: ‘Stars, that’s what we were.’ Another observes:

‘Whenever Europeans looked at us their eyes shone. Now I understand why. It was with desire, because their looking at us produced a reaction on our bodies before we realized it. Even with our backs turned we could feel your eyes drilling through the backs of our necks. We automatically adopted a heroic and therefore attractive pose. Legs, thighs, chest, neck – everything helped to work the charm. We weren’t aiming to attract anyone in particular, but since your eyes provoked us and you’d turned us into stars, we responded to your hopes and expectations.’

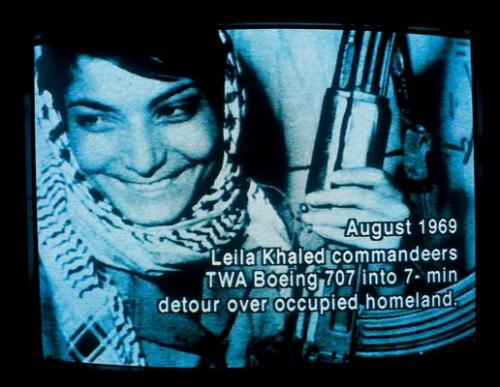

The same Fedayeen continued: ‘But you’d turned us into monsters, too. You called us terrorists! We were terrorist stars.’ (Jean Genet, Prisoner of Love, New York Review Books, 1986) This condition of being imaged and being aware of being imagined has followed the Palestinian struggle at least since the 1960s. But the awareness of Palestinians that they are the subject of media representation was not just a matter of being aware that they had been turned into different kinds of stereotype – the guerrilla hero, or the terrorist monster, or, in addition to the two figures discussed by Genet, the refugee victim – stereotypes that service the desires of others. This awareness has also related to how Palestinians have seen that the media can also serve them. Through spectacular acts of symbolic violence Palestinian fighters thought they could gain the attention of the media to their cause, using the limelight to tell the story of the Palestinian catastrophe to a world that did not appear to know, or did not seem to care. This is demonstrated by the TV footage contained within artist Johan Grimonprez’s film about the history of skyjacking dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y (1997) in which Palestinian guerrillas were allowed to speak to the press about their cause after they were arrested.

But this need to connect with a media public was not just a matter of making visible something that has been marginalised within the field of vision, it also logically involves the assumption that the audience, or at least some of that audience would empathise with the Palestinian plight. Israeli writer Ariella Azoulay has defined this empathetic connection as one involving a ‘civil’ relationship between people who are linked by an understanding of citizenship that exceeds the civil status granted by sovereign power. Discussing photographs of Palestinians living in the occupied territories, Azoulay has observed:

‘The consent of most photographed subjects to have their picture taken, or indeed their own initiation of a photographic act, even when suffering in extremely difficult circumstances, presumes the existence of a civil space in which photographers, photographed subjects, and spectators share a recognition that what they are witnessing is intolerable.’ (Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography, Zone Books, 2008)

In relation to Bil’in, this sense that the presence of the visual media at the demonstrations connects the villagers with people that can recognise that what is being done to the village is wrong is shown by the example of a demonstration for which village children produced a poster that depicted a camera and bore the slogan in English: ‘Their eyes won’t stop showing the Israeli soldiers crimes.’

This slogan suggests that there are people out in the wider world who will also see the things shown in photographs of the struggle in Bil’in and elsewhere in the occupied territories as a crime, that these people are connected to the makers of the poster by a shared understanding. This sense of a shared civil ethos is also suggested by Mohammed Khatib’s call to others to ‘Please stand with us.’ But here the call is not for people to simply recognise something, but to act upon this recognition and to do something to help the people of Bil’in in their struggle. Here the connection that mediation allows is not just about publicity, or even about keeping the popular struggle in Bil’in in the public eye so as to afford some degree of protection, but a matter of creating a bigger community of concerned citizens and even activists with whose help the people of Bil’in might have some hope of succeeding in the goal of regaining the land they have lost to the construction of the barrier and to the expansion of the nearby settlement of Modi’in Illit. In these terms the dissent events in Bil’in are only really completed when they lead to something else, that is, to action and practical political results.

Good day,

Hope you don’t mind, but we shared ur post in

http://www.facebook.com/GHASSAN.KANAFANI

By: Taz on September 26, 2010

at 11:30 am

[…] Simon’s Teaching Blog [2] http://www.bilin-village.org This entry was posted in Uncategorized. Bookmark the […]

By: Bilin Village | Middle East Crisis, History and Politics on September 26, 2010

at 8:27 pm

Thank you for the informative post. Got me thinking a lot.

By: Bella of Tuition Centre in Penang on October 18, 2010

at 2:26 pm