The following paper was delivered at the ‘Social Media and Political Horizons: Israel/Palestine, the Middle East and Beyond’ workshop, organised by Adi Kuntsman and Rebecca Stein at The University of Manchester, June 2013.

I should state from the outset that my paper is not really about social media. Nor is it really about the Israeli military. It touches on both of these subjects, but it is really about something else. In fact I am not really interested in social media, or the Israeli military per se. What I am interested in is images, or more precisely in how they are put into motion, how they get shifted from one context and from one form to another. This means that I am interested in what Hans Belting defines as the nomadic nature of images (see Hans Belting, An Anthropology of Images: Picture. Medium. Body, Princeton University Press, 2011; first published in German in 2001). This is an old subject. It is the classic interest of art historical iconography, as exemplified by Aby Warburg’s early twentieth century ‘Mnemosyne’ project (see Philippe-Alain Michaud, Aby Warburg and the Image in Motion, Zone Books, 2004). However this old subject remains relevant to the contemporary period when digital cultures and social media define significant contexts for the image in motion. Iconographers thought that by tracking the movement of images across time and space they could understand important aspects of cultural memory and define how certain recurrent motifs become the loci of key social narratives. Here we are also touching upon the subject of iconic motifs and cultural icons of the kind addressed by scholars such as Robert Hariman and John Lucaites (see Robert Hariman and John Lucaites, No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy, University of Chicago Press, 2007). Such work suggests that visual images are put in motion – through their replication and adaptation over time – because we care about them, because they have significant meaning, or value, because they do something for us. These points also relate to discussions of technological reproduction of the visual image articulated by Walter Benjamin in the 1930s (obviously I am referring to ‘the work of art’ essay here) and by John Berger after him in the early 1970s (obviously I am referring to the first episode of Ways of Seeing). In one sense the replication of digital images in the contemporary period is a further extension and intensification of the photographic reproduction discussed by these earlier thinkers.

To think about the image in motion it is necessary to consider what is meant by the term image. Again I follow Belting when he defines images as motifs that can exist in different ways. They can be in our heads, or as Belting puts it, in our bodies. They can take the form of words. And they can take the form of pictures, which is where Belting suggests that the image/motif is made visible through a medium (in his terms the image ‘resides’ within the picture/medium). When we talk about images we usually mean pictures – and when it comes to social media, for example, this usually means photographs – but a picture is just one manifestation of an image. The technical reproduction of pictures, whether analogue or digital, is one way that images move. But they also move in Belting’s terms between the picture and the viewer: between the external pictorial image and the internal image. Thus Belting observes that an image often ‘straddles the boundary between physical and mental existence.’ And it is this kind of movement between a picture and the mind that enables the production of new, or adapted pictures that are generated in response to what the spectator sees and understands of the original. Pictures move, but the point is that the picture does not have to move for the image to move.

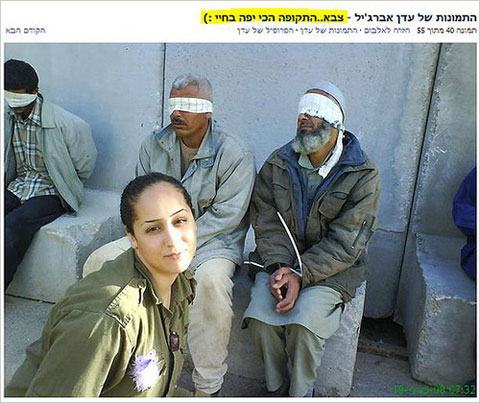

All of this leads me onto a subject more directly relevant to the theme of this seminar. This is the furore around the posting of certain photographs on Facebook in August 2010 by the former Israeli soldier Eden Abergil. Various people have written about this subject, including Adi Kuntsman and Rebecca Stein in their book Digital Militarism. Right now I am not sure what I will have to add to these discussions, other than a sense that it is important to consider this subject in terms of the idea of the image in motion. And that something of the ‘viral’ nature of the furore around the Abergil pictures can be understood by adapting long-standing iconographical approaches.

The Abergil photographs are of her posing in front of handcuffed and blindfolded Palestinian detainees in Gaza. But they are also more than this in that they have been read as representative of power relationships between the Israeli occupier and the occupied Palestinians. The movement of these pictures as images was therefore both the literal movement of the digital photographs and also the movement of a motif that in Belting’s terms is not necessarily limited to any one medium, or even to a medium at all.

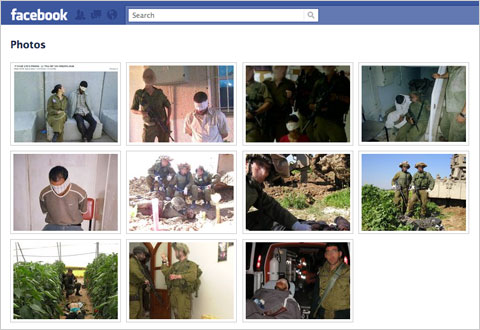

The original pictures started out as digital photographs on a phone, or a camera that were then posted on Facebook as part of a set of ‘snaps’ and ‘selfies’ depicting Abergil and her army friends under the heading ‘The Military – the Best Time of My Life’.

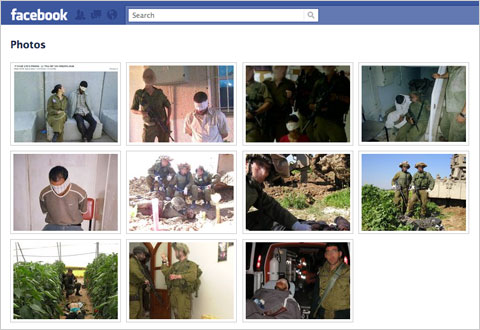

It was from this larger set of photographs that the two pictures of Abergil posing with the detainees were selected and relocated on blogs, websites, and off-line in newspapers. The Israeli NGO ‘Breaking the Silence’, for example, reframed the pictures in a different set of photographs that depicted other Israeli soldiers posing with blindfolded, or dead Palestinian men.

In this way, the Abergil pictures became part of a set that was not about ‘good times’, but explicitly about oppression, abuse, and violence. In the process they were redefined as part of the photographic sub-genre of soldier’s trophy pictures (see Janina Struk, Private Pictures: Soldier’s Inside View of War, I. B. Taurus, 2011). Other people compared the Abergil pictures to the photographs from the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq during the US occupation as a measure of their oppressiveness. In addition to all this, the image of Abergil herself was also transformed into a meme involving the superimposition of her portrait onto pictures of famous historical events, some of which were violent and traumatic.

Here there was a dislocation of Abergil’s likeness from the frame of the occupation, but what remained was the sense of her making light of a scene that should not be made light of.

The Abergil pictures – as manifestations of a more generic motif of the oppressiveness of the occupation – moved in other ways. At the end of the week in which the pictures broke as an international news story they were referenced within the weekly Friday demonstration against the West Bank Barrier in the Palestinian village of Bil’in. This enabled the activists of Bil’in and their supporters to mobilize the current notoriety of the Abergil affair and also to refer to the ongoing detention of fellow village activists. Demonstrators playing the role of blindfolded and handcuffed detainees walked from the village, before sitting down in front of a line of soldiers and in front of attendant members of the media. This action was an image itself, but at the same time it was intended to enable the production of further mediated images. These pictures ended up in newspapers, on blogs and as video on YouTube, specifically a video made by the Israeli video-activist David Reeb.

In relation to this YouTube video we can see that one trajectory of the Abergil pictures as images was from one social media platform to an off-line event and then via the ‘documentary aftermath’ (see Imogen Tyler, Revolting Subjects: Social Abjection and Resistance in Neoliberal Britain, Zed Books, 2013) of this event, back onto another social media platform. But the aftermath of this protest event was not just a documentary one. From one of the stills from his video, Reeb made a painting entitled Facebook Painting; a title that made the reference back to the Abergil pictures more explicit than the picture itself.

This relative lack of explicit visual reference to the original pictures was compensated for during the demonstration when one Palestinian demonstrator declared to the line of soldiers: ‘Now you get a picture, you can put it in your Facebook.’ While another stated: ‘If any soldier has Facebook, you take this picture to Facebook’.

Reeb’s painting takes an image of the demonstration and remakes it through the process of painterly production. The light and shade and colors of the documentary image become the basis for what he defines as the ‘absurd’ act of covering a canvas with paint. The painting also includes members of the press within its pictorial frame, depicting actors who are not usually shown within pictures of protests against the occupation, or for that matter in documentary and press imagery in general. In this way the painting appears to be concerned with the image-making nature of such demonstrations. Such a concern might also be linked to the history of reflexiveness towards the practice of picturing that is part of the history of painting.

There is another thing that interests me about the movement of the original Abergil pictures and the inter-visual relationships that this involved. This interest is not in the figure of Abergil and what she did, but more in the blindfolded Palestinians in the pictures. That is, in the blindfolded Palestinians as a recurrent visual motif of the occupation.

Imagine the Abergil pictures without Abergil and they become just one more image of detained Palestinians. When the focus is on Abergil, this standard image of the occupation somehow loses significance. The furore around the Abergil pictures concentrated upon the ethics of what she had done and her actions as an indication of some kind of oppressive excess. This happened both when the IDF defined this excess as abnormal in relation to their standards of military conduct and when ‘Breaking the Silence’ argued that this excessive behavior was a regular thing within the occupied territories. What disappeared a bit from view was the normality of this Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) of detention as part of the military structure of the occupation. Through the movement of the Abergil pictures something of the occupation seems to have become visible, but at the same time something, perhaps more significant, was rendered less visible.

The question I would want to ask is: if you took the posing figure of Abergil out of this picture, would it really be any less bad? Are the hundreds of other pictures of blindfolded and handcuffed Palestinians ok when the figures of posing Israeli soldiers are absent? My suggestion would be that the answer to both these questions is no. And moreover that the pictures of detained Palestinians that are just routine, that do not generally cause any great fuss, take us more to the heart of the procedural oppressiveness of the occupation than Abergil’s posing. While referring back to the original Abergil pictures, the demonstration in Bil’in also invokes these standard images of Palestinian detention and as such it resonates with other demonstrations that referenced the standard mode of detaining Palestinians in the occupied territories.

ActiveStills, Protest outside the Tel Hashomer army recruitment base, near Tel Aviv, September, 2005

The Bil’in demonstration exploited the news value of Abergil, but also made visible the SOP of detention. It turned this SOP into an image that was performed and made this performance news.